OTTOMAN EMPIRE

1517 - 1917 AD

(photo Damascus gate 1900)

OTTOMAN EMPIRE OCCUPIES ISRAEL

1517 AD -1917 AD

The Ottoman Empire, spanning from the 14th to the early 20th centuries, was a vast global empire that conquered and controlled significant territories in Southeastern Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa. Its origins can be traced back to the late 13th century in northwestern Anatolia (present-day Turkey), where Osman I founded it. In 1516-17, Turkish Sultan Selim I defeated the Byzantines in the Holy Land, resulting in the incorporation of the region into the extensive province known as 'Ottoman Syria' for the following four centuries. It's worth noting that while Palestine is a commonly used name, it wasn't an official designation in the Ottoman Empire.

_(07)%20(1).jpg)

Photo by Chris06

Under the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, the empire experienced its pinnacle of power, marked by prosperity, as well as cultural and political influence. During this era, the influence of Islam was prominent, leading to strict prohibitions on the construction of churches and synagogues in certain locations. In Jerusalem, for instance, The Cenacle, the site of the Last Supper and the earliest church in the city, was confiscated and converted into a mosque. However, in other areas, Jews and Christians enjoyed certain rights under their 'dhimmi status' and were permitted to construct or rebuild synagogues and churches for their respective communities.

The architectural influence of the Ottoman Empire is still evident today, particularly in the renowned walls of the Old City of Jerusalem. These impressive walls were constructed between 1535 and 1542 under the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. While the new walls largely followed the path of the original ancient walls, they excluded the City of David and the area now known as Mount Zion. Suleiman the Magnificent's efforts significantly enhanced safety and stability in the Ottoman provinces, leading to remarkable development and growth during the 16th century.

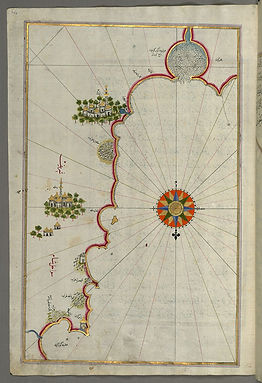

Piri Reis - Map of the "Syrian Coast", "Gaza & Ramlah" (1525) - Walters Museum W658312A (wikimedia)

The renowned Ottoman cartographer 'Pīrī Reʾīs bin Ḥājjī Muḥammed', better known as 'Piri Reis', referred to the area as the “Syrian coast” in his exceptional Kitāb-i Baḥriye (“Book of Navigation”), originally composed in 1525 CE.

The Ottoman Empire was divided in administrative provinces that were named Eyalets, Beylerbeyliks (see map) or Pashaliks. The Eyalet 'Syria' was divided into five Sanjaks: Safad, Jerusalem, Nablus, Lajjun, and Gaza. However, in 1660, Koprulu Mehmed Pasha reorganized the province into three Eyalets. The Sidon Eyalet encompassed Acre, while the Safad Eyalet and Damascus Eyalet, centered around Jerusalem, were established. In 1865, the Ottoman region underwent another reorganization, resulting in the Vilayet of Syria and the Mutassarifate of Jerusalem. Syria was further divided into Gaza, Damascus, Acre, Tripoli and Aleppo.

Map of 17th-century Ottoman Syria, incluuding the Eyalets of Damascus, Tripoli, Aleppo and Rakka.

15th C. Abuhav Synagogue, Safed Photo:Israel Toerism

SAFED & TIBERIAS REVIVAL

There were significant migration events during the Ottoman era, particularly in the 15th and 16th centuries when Sephardic Jews from Spain sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire due to the Inquisition. On May 1, 1492, the Spanish King issued the Edict of Expulsion, which mandated the expulsion of Jews from the Kingdom, forbidding their return unless they converted to Christianity. Many Jews migrated to the Ottoman Empire, with a substantial number eventually settling in Israel. During this time, numerous influential rabbis also traveled to Israel, such as Rabbi Yehiel Ashkenazi, who journeyed from Italy and became the leader of the Ashkenazi Jews in Jerusalem.

However, violence also occurred within the Ottoman Empire during this period. In 1517, the Jewish community in Hebron was destroyed, and in Safed, many Jews were killed by Arabs who turned against them. Safed, nevertheless, quickly recovered and became a vibrant center for Jews in the 16th century, boasting over 30 synagogues and hosting many prominent rabbis. In this "golden age" of Safed, Rabbi Yaakov Beirav brought an ancient Torah scroll to the city, which is still preserved in the beautiful Abuhav synagogue. Other exiled rabbis from Spain, such as Rabbi Moshe Trani and Yosef Caro, also resided in Safed. Notably, Rabbi Isaac Luria, Joseph Vital, and Moses ben Jacob Cordovero played a significant role in reviving Jewish interest in Kabbalah. Yosef Caro made a substantial contribution to the development of Judaism by authoring the important work known as the "Shulhan Aruch" in Safed. Additionally, in 1577, Safed became the site of the first printing press in the Ottoman Empire, established by Eliezer B. Isaac Ashkenazi, who migrated from Europe to Safed. The Jewish community in Hebron also recovered despite remaining far smaller than in Jerusalem and Safed. Solomon Adeni who was born in Yemen wrote Melekhet Shelomon, a commentary on the Mishnah in Hebron.

GRACIA MENDES : SAVIOUR & 'RETURN TO ZION'

Gracia Mendes Nasi (1510 – 1569) was a wealthy Portuguese-Jewish woman and one of the most influential and affluent Jewish figures in Europe during the 16th century. She was the aunt and business partner of João Micas, also known as Joseph Nasi in Hebrew, who rose to prominence as a significant political figure in the Ottoman Empire. Their efforts were instrumental in providing refuge to Jews fleeing the harrowing Spanish Inquisition.

Gracia Mendes Nasi played a pivotal role in saving hundreds of Jews by facilitating their escape from Spain and other European countries. Through her connections and influence, she obtained permission from Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to restore the ancient Jewish cities of Safed and Tiberias. Gracia also assisted Jews in their journey to these sacred Jewish cities, making her a precursor to the Zionist movement that emerged in the 19th century.

Joseph Nasi aimed to establish a silk production center in Safed, and both Gracia and Joseph achieved some success in their endeavors. However, they faced resistance from local Muslims and Druze communities who opposed their efforts to rebuild the city.

Picture of Wikimedia commons of Gracia. Graça (Portuguese) or Gracia is Spanish for the Hebrew name Hannah, which means Grace.

JERUSALEM SUFFERS UNDER THE PASHA MUHAMMED IBN FARUK

.png)

In the early seventeenth century, Jerusalem’s Jewish community experienced a period of remarkable vitality. Synagogues, schools, and Torah study flourished, supported by generous donations from abroad and guided by distinguished leaders such as Rabbi Isaiah HaLevi Horowitz, known as the Shelah. This prosperity was abruptly shattered with the rise of Muhammad Ibn Faruk, a corrupt and brutal governor who seized control of the city by force. Supported by mercenaries, Ibn Faruk imposed a regime of extortion upon Muslims, Christians, and particularly Jews. Community leaders were imprisoned and tortured, synagogues and schools closed, and access to the Western Wall was denied. For two years, Jews were forced into hiding, reduced to poverty and crippling debt as they borrowed at exorbitant rates to ransom their rabbis and elders. aAlso the Christians in Jerusalem suffered greatly as Ibn Faruk tried to blackmail the local Franciscan monastery and forced the Christian leaders to flee Jerusalem. The situation deteriorated further when Ibn Faruk openly rebelled against the Ottoman sultan, intensifying his persecution of the Jews. Hostages—including rabbis and physicians—were tortured while the community starved. Yet his downfall, according to contemporary accounts, came not through imperial intervention but through a dream in which King David warned him of impending death should he remain in Jerusalem. Terrified, Ibn Faruk fled the city in 1626, taking plunder and captives, though the hostages were soon released (see link). The Jews of Jerusalem rejoiced at their deliverance, yet their relief was tempered by immense debts and a community reduced by nearly seventy percent.

Historian Eldad Zion notes that the Jews of Jerusalem viewed their ordeal through a messianic lens, interpreting suffering as a prelude to redemption. The Shelah himself initially refused to leave, regarding residence in the holy city as a sacred duty that might hasten salvation. Only after imprisonment and release did he flee to Safed and later Tiberias, where he died in 1630. Although Ottoman Jerusalem often suffered under corrupt rulers, Ibn Faroukh’s greed and brutality were exceptional. His short but devastating rule left the Jews impoverished and dependent on support from the wider diaspora, yet their resilience and hope for redemption endured.

CHRISTIANS IN THE 16TH & 17TH CENTURY

Saints Nicholas Church with a 5th-6th century Crypt in Beit Jala. Beautiful picture by SalibaQ

In this early Ottoman period the Christians continued to survive in the Holy Land and in Jerusalem and their numbers were even growing. On a limited scale they were able to rebuild and restore some churches. Sadly since the establishment of the Ottoman Empire, the reconstruction of churches and synagogues, particularly in Jerusalem, were prohibited or faced significant restrictions. However Ottoman taxregisters (see link) confirm that significant populations of Christians lived in Jerusalem, Bethlehem and Beit Jala. The largest Christian groups were The Greek Orthodox Christians. In Jerusalem the Greeks Orthodox were the biggest Christian group, followed by the Armenians, Jacobite Syrians, Maronites, Copts and a few Catholics. In 1672, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Dositheus II, organized the Synod of Jerusalem, which is also known as the Synod of Bethlehem since it coincided with the consecration of the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem. The primary objective of the Synod was to condemn Calvinist influences within the Orthodox Church. Attended by prominent representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Synod's decrees gained widespread acceptance throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church.

EARLY 1700 & ASHKENAZI MIGRATION

During the 18th century, life for the "dhimmis" (Jews and Christians) was challenging, and the development of Jewish and Christian communities continued to face severe oppression. Migration was largely prohibited but still there were some instances of migration. Yehuda He'Hassid led approximately 1500 of Jews from Poland to Israel on the 14th October 1700. The Jews joined the Jews that lived in Jerusalem but their sudden influx created a crisis for the Jewish community in Jerusalem. Yehuda He'Hassid died within days of his arrival and was buried on Mount Olives. Some of the new migrants moved to Tiberias, Hebron or Safed. Others stayed and eventually helped to rebuild the Jewish community in Jerusalem. The reconstruction of the famous Hurva Synagogue, which took place between 1701 and 1720, required significant payments and bribes to obtain permission. Once completed, the Jewish community was burdened with heavy taxes they could not afford to pay. In 1721, Muslim leaders looted the silver from the synagogue and set it ablaze.

This dramatic event serves as an illustration of the functioning of the Ottoman Empire, as described in Alan Dowty's book, "Arabs and Jews in Ottoman Palestine." Dowty analyzes the primary focuses of the Ottoman Empire, which were tax collection and armed conscription. Only a few local Arabs held high positions in Turkisch-Ottoman administration, and the local population did not strongly identify with an Ottoman identity but rather focused on their daily lives and immediate communities. Local sheikhs and rulers kept the majority of the taxes for themselves and aimed to extract as much tax revenue as possible. Subsistence agriculture remained the economic foundation until the reorganization efforts of the Tanzimat in the 1830s. Consequently, the Ottoman provinces, or Sanjaks, remained impoverished, desolate, and sparsely populated due to the absence of a strong government that could guarantee the safety of its people.

Abraham Avinu Synagogue, 1540 AD, Hebron

Al Bahr Mosque, 1675 AD, Jaffa.

Photo: Godot13

This depiction aligns with the observations made by Adriaan Reland, a professor in Oriental Languages at the University of Utrecht. Reland's work, "De religione Mohammedica libri duo," completed in 1705 and expanded in 1717, was regarded as the first objective survey of Islamic beliefs and practices. In his publication "Palaestina ex monumentis veteribus illustrata" (1714), Reland described and mapped the geographical features of biblical-era Palestine based on his extensive travels in 1695. According to Reland, the land in 1695 was sparsely populated, with Jewish origins clearly evident in all towns and cities. The presence of both Jews and Christians were the most influential and prominent in Ottoman Palestine at the end of the 17th century. The Arabs mentioned by Reland were predominantly Bedouins, and Reland did not reference significant Muslim sites or monuments.

Despite economic hardship in the region in the 18th century, the connecting between Jews in 'Eretz Yisrael' and the diaspora remained strong and migration continued. A notable wave of migration took place in 1765 when Rabbi Menachem Mendel of Vitbesk, one of the leaders of the Chassidic movement, emigrated from Eastern Europe. He, along with a group of several hundred followers, settled in Tiberias and established new synagogues.

DAHER EL-OMAR: COEXISTENCE & SEMI-INDEPENDENCE IN THE GALILEE AND SOUTHERN LEBANON

Daher el-Omar, also known as Zahir al-Umar (born 1690, died August 21, 1775), was an Arab-Bedouin ruler who governed the Galilee district of the Ottoman Empire during the mid-18th century. He played a significant role in shaping modern Haifa and fortified cities such as Acre (as depicted in the beautiful painting). Zahir al-Umar aspired to establish an autonomous region within the Ottoman Empire, and to some extent, he achieved this goal.

His rule began in the 1730s, primarily in the northern regions of Israel (the Galilee) and the South of Lebanon. He gradually expanded his vazal-state and shortly conquered Damascus. He was a smart ruler who was supported by his family but also by Melkite Christians and he skilfully managed to develop the region with a more efficient administration and stronger economy. This gave him the resources to pay taxes to the Ottoman Sultan but also govern the region successfully as a semi independent state for a quarter of a century. However, when the Ottomans entered into a truce with the Russian Empire and the Ottoman government gained a sense of strength, this period came to an end. In 1775, the Ottoman Navy launched an attack on Zahir's headquarters in Acre, resulting in his death shortly thereafter.

Daher al Omar, photo by Ziad Daher

In a remarkable tale of peaceful coexistence, Rabbi Chaim Abulafiah, a Kabbalist, migrated from Istanbul to Tiberias in 1740. This move was made possible through the invitation and support of Daher al-Omar. With the backing of Omar, Rabbi Abulafiah played a pivotal role in revitalizing the Jewish community in Tiberias. Al Omar helped the Rabbi build the Jewish Quarter in the center of the Old City of Tiberias. Surrounded by Muslim quarters, the relationship between neighbours were very good. This peaceful coexistence defined Tiberias for over 200 years. The Jewish leadership, led by the prominent Sephardi families of Abulafia and Alhadif, maintained good relations with the Arab residents, led by the rich and powerfull al-Tabari family. Rabbi Abulafiah built yeshivas and synagogues that can still be visisted in Tiberias today. (see link)

In addition to migration restrictions, Jewish and Christian communities faced hindrances to their growth due to various natural disasters. Devastating plagues in 1742 and 1812 claimed numerous lives, while massive earthquakes in 1769 and 1837 resulted in the destruction of many ancient synagogues (such as in Safed) and churches. Despite these catastrophes, the communities managed to endure, and new communities were even established. Probably the communities managed to survive in times of severe poverty by asking other Jewish Communities (in Egypt, Turkey and Italy) for financial help. A millennia old practice that is clearly visible in the 18th and 19th century letters in the Cairo Genizah (See Safed,Jerusalem&Hebron & 19th C. letters). Another 18th century example of the continuous religious ties between the Jews in Europe and 'Eretz Ysrael' is the pilgrimage of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. This famous Rabbi was an inspirational figure for the Hasidic movement, combining Kabbalah with Torah study. He was influential within the Jewish community in Tiberias in the 18th century. He attracted thousands of followers and his influence continues today within the Hasidic community. Between 1798 and 1799 he went to Israel, where he was received with honour by the Hasidim living in Haifa, Tiberias, and Safed.

Ketubbah (Jewish Marital contract) from 1750, depicting Jerusalem

Beautiful quote from Rabbi Nachman: Worldly desires are like sunbeams in a dark room. They seem solid until you try to grasp one.’

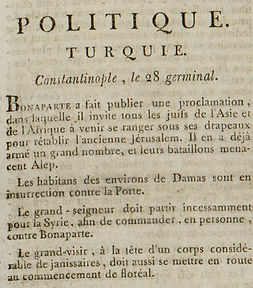

NAPOLEON CONQUERS JAFFA

Bonaparte visiting the plague victims of Jaffa

In 1799, a significant event unfolded when Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Jaffa, initially appearing as a colonial conquest. However, it is important to note that prior to this, Napoleon had already made notable strides in the liberation of Italian Jews. He gained acclaim by abolishing the ghettos in Italy between 1796 and 1797, granting Italian Jews equal rights of citizenship and enabling their participation in governmental roles. Furthermore, Napoleon's conquest extended to the powerful island fortress of Malta, which was previously held by the Christian Order of the Knights of Saint John, an institution known for its anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish sentiments. Upon taking control, Napoleon swiftly liberated Muslims and Jews who had been enslaved. He not only established Jewish civic rights but also upheld the right to practice Judaism in synagogues. Embracing the ideals of the French Revolution, Napoleon aimed to free the Greek, Jewish, and other indigenous Mediterranean populations from the grasp of the Ottoman Empire. He even advocated for their right to have their own states, as exemplified in his declaration pictured below and in the provided links. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that despite these progressive intentions, Napoleon's methods of achieving his goals were far from modern or humane. Tragically, in the course of his conquest, he resorted to brutal acts of violence, including the ruthless slaughter of Muslims in Jaffa.

RESPONS BY THE JERUSALEM JEWS

When Jewish Sephardic community in Jerusalem heard rumours of the advancing Frech army. The Jews feared that Napoleon would conquer Jerusalem and this would spark serious violence of the Arabs. Rumours circulated that some local Jews might side with Napoleon, though no broad support materialised. In reality, Jews in Jerusalem publicly affirmed their loyalty to the Ottoman authorities and they actively helped organise the city's defence, including bolstering fortifications. Yom Tov Algazi, then a senior Sephardic rabbi in Jerusalem, led the community in prayers for Ottoman victory at the Wailing Wall and helped assemble a Jewish contingent for defence, reinforcing Jerusalem’s alignment with the Ottomans rather than Napoleon

OTTOMAN PERSECUTION OF THE SAMARITANS

During the Ottoman rule of the region the Samaritan community in Egypt was severely persecuted, leading to widespread conversion to Islam. In Damascus, many Samaritans were either massacred or converted during the rule of Pasha Mardam Beqin in the early 17th century. The remaining Samaritans fled to Nablus in the 17th century. Muslim persecution continued in the 17th century, resulting in violent riots and mass conversions and in the mid-17th century, only small Samaritan communities persisted in Nablus, Gaza, and Jaffa.

In the 1840s, the Ulama from Nablus contested the Samaritans classification as "People of the Book," advocating for either the killing the Samaritans or their conversion to Islam. Despite appealing to the King of France, the situation persisted until the Samaritans asked for help from the Jews. Rabbi Chaim Abraham Gagin wrote a document that the Samaritans are a "Jewish sect". This declaration ended the ulama's opposition, but Samaritans still had to pay large bribes to the Arabs for protection. The pressure to convert, persecution, and natural disasters resulted in the late Ottoman period into the smallest Samaritan community with approximately 100 people left.

Chaim Abraham Gagin (1787–1848) was born in 1787 but became the Chief Rabbi of Ottoman Palestine from 1842 to his death in 1848. He was the grandson of the Jerusalem Kabbalist Shalom Sharabi. He was also the author of Sepher Hatakanoth Vehaskamoth, a compendium of Jewish religious rites and customs as practiced in the City of Jerusalem.

(Tzemach Tzedek Synagogue 1858 AD in Jerusalem)

TANZIMAT', MOHAMMED ALI & REVIVAL OF NON-MUSLIM COMMUNITIES

_svg.png)

The 1830s brought significant upheaval for Jews living in the Land of Israel amid sweeping reforms and violent uprisings. Under Ottoman rule, the Tanzimat reforms sought to centralize power by modernizing schools, courts, and taxation, reducing the influence of local sheikhs. In 1831, Mohammed Ali of Egypt embarked on a campaign to conquer significant portions of the Arab world. When his son and general Ibrahim Pasha took control of Ottoman Syria, new reforms further destabilized the region. These changes, including tax equality and military conscription, upset traditional social hierarchies that had long privileged Islamic elites and exploited non-Muslims, sparking widespread resentment among Arab and rural leaders. The tensions combined fueled antisemitc violence and pogroms that will be discussed later.

.jpg)

Oldest Ottoman Hammam (1800 AD)-Photo: Yazeed Tamimi7

.jpg)

Ibrahim Pasha, son of Muhammed Ali, led the Egyptian army in the Levant. (Wikimedia C.)

Mohammed Ali enjoyed considerable success in defeating the Ottoman army on multiple occasions. However, the intervention of the British navy eventually led to a brokered peace in 1842. Mohammed Ali withdrew from the Levant but, in return, he and his descendants were granted hereditary rule over Egypt and Sudan. Ottoman rule was reinstated in the Levant, while European nations received significant privileges, paving the way for a resurgence of Christian religious life in Israel and with the strict Ottoman limitations on migration coming to an end also Jewish immigration and the construction of synagogues became more feasible.

When these Ottoman restrictions on the rebuilding of non-Muslim religious structures were lifted it enabled the restoration and reconstruction of many ancient churches and monasteries and the revitalisation of Christian communities in Israel. A fascinating example are the Armenians in Jerusalem who were pioneers in introducing the printing press and photography to the city. The St. James Armenian Printing House, established in 1833 at the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, was the first printing house in the Middle East. Consequently, the first book printed in Jerusalem was in Armenian. The museum features a replica of Gutenberg’s original printing press, thought to be the first such machine used in Jerusalem. (See photo by Israel Zeller).

SAFED POGROMS OF 1834 AND 1837

In 1834, this discontent erupted into the Peasants’ Revolt, targeting Egyptian rule and reform policies. In cities like Nablus, Hebron, Bethlehem, and Safed, Jews became primary victims of the violence. In Jerusalem, a siege by Arab peasants against Egyptian troops began in May but was crushed by Ibrahim Pasha’s forces by early June. Meanwhile, in Safed, the violence took on the character of a pogrom. On June 15, incited by a local preacher, Muhammad Damoor, Arab and Bedouin attackers massacred over 500 Jews, raped women, looted homes and synagogues, and desecrated Torah scrolls.

A letter from Safed to the Jewish community in London in 1834 serves as evidence of these horrifying events. Fortunately, most Jewish inhabitants managed to escape this catastrophe by fleeing until order was eventually restored a month later by Ibrahim Pasha's army. According to Neophytos, a monk from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, similar looting and violence occurred in other towns, including Ramle, Lydda, Jaffa, Acre, and Tiberias. He described how the perpetrators "robbed the Jews, who lived in these towns, of immense property, as is reported, for there was no one to offer any opposition."(See link). The pogrom ended after Rabbi Israel of Shklov appealed for foreign intervention and Emir Bashir ultimately suppressed the violence, but the Jewish community was left devastated, recovering only a fraction of its losses.

The violence in Safed resurfaced in August 1838 when Druze rebels, supported by Arabs, launched another brutal attack. Over three days, Jews were murdered, homes looted, women assaulted, and synagogues desecrated. Many fled to safer cities, and those who remained faced extortion and ruin. This pogrom echoed the sectarian violence seen in the 1860 Druze massacres of Christians in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, which caused a mass exodus of Christians from the region.

JEWS & ANTISEMITISM IN CHANGING OTTOMAN EMPIRE

These events underscored the precarious position of Jews in the Land of Israel during a time of political reform and upheaval. While the Tanzimat and Egyptian policies aimed to modernize and equalize, they provoked fierce resistance that turned Jews into scapegoats, leaving their communities scarred and struggling to recover. Also the condition of Jews in Muslim societies was governed by the pact of Umar, which assigned non-Muslims, including Jews, the status of dhimmis"protected" but inferior and subjugated subjects bound by discriminatory laws and taxes. Rooted in Quranic verse (9:29), dhimma created a two-tier society, with Muslims as dominant "masters" and non-Muslims relegated to an inferior status.

In 1856 followed the very important (Hatt-i-Humayun) decree from Sultan Abdülmecid I promised equality in education, government appointments, and administration of justice to all ending the discrimination on the basis of religion, language or race. However, fearing to much western influence the Ottomans started with promoting their state ideology of 'Ottomanism' through education in the thousands of government schools. Despite the Tanzimat, The Ottomans however never managed to create a strong centralised government and according to John Murray in his 'Handbook for travellers in Syria and Palestine' (1858) this enabled the local Arabs to maintain their local power often resulting into violence and a state of semi-rebellion. Also the Christian and Jewish minorities were insulted and oppressed and Murray describes how an Arab citizen from Shechem shot a Jewish boy in his shop.

Historians Janine and Dominique Sourdel note that this structure fostered intolerance towards religious minorities in strict Muslim states (see link). In the 19th century, numerous accounts highlighted the contemptuous treatment of Jews in Arab-Muslim lands, where coexistence was fragile and violence, including bloodshed, was used to enforce social hierarchies. For example, a 1910 traveler to Yemen described Jews as scapegoats subjected to arbitrary abuse. Israeli historian Amnon Cohen's study of Islamic court archives in Palestine shows that the dhimma, formalized in the "Pact of Umar," remained a rigid and coercive system for centuries, unilaterally imposed on subjugated populations.

Two Rabbi's in Jerusalem, 1856, Alexandre Bida (Wikimedia Commons)

MIGRATION AT THE END OF THE 19TH CENTURY

At the end of the 19th century, between 1881 and 1914 more immigrants arrived. More than 2,5 million Jews migrated from Eastern Europe fleeing prosecution or they fled violence in Russia and the pogroms in the years of the Russian revolution. Most went to the US but migration to Ottoman Syria (Judea and Samaria) also grew rapidly. During the first Aliyah (called Aliyah of the Farmers) in the years 1881-1903 more than 28 communities (moshavim) where started (for example Mazkeret Batya). These new immigrants started new communities or joined the existing communities from Yiddish speaking Ashkenazim (from Eastern Europe) and Ladino-speaking Sefaradim (from Spain and Portugal). The impact of this new immigrants was huge. Economic growth was clear but also Jewish influence on Israel began a real revival.

A very large group immigrants were Jews from the Middle East. Yemite Jews arrived in 1882 Jews and the first wave of Iranian immigrants (mostly from Shiraz) arrived in 1886 in Jerusalem, inspired by Rabbi Aharon HaCohen. They had made exhausting and dangerous travels on foot, camels and ships with women and children. These 'Parsim' with their strange language, exotic customs and middle east appearance, were very religious practising Jews that build communities and synagogues in and around Nahlaot neighbourhood of Jerusalem. This highly multicultural but Jewish part of Jerusalem also became the home for Syrian, Kurdisch and Uzbek Jews.

.jpg)

Stella Maris Monastery founded in 1846 AD (photo Inbal Bar)

CHANGING OTTOMAN EMPIRE & REVIVAL OF CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES

The Armenian Orthodox community in Jerusalem made important contributions to the city when the first printing press in Jerusalem was opened by Armenians in 1833. Not only were more than 1200 titles of books published with this press (In the nearly two hundred years that passed) but many local Armenians in the nineteenth century started businesses in printing, typesetting, and bookbinding. This thanks to the skills they could learn with this printing press. This remarkable facts shows Jerusalem was relative undeveloped during the Ottoman occupation. In general the whole region during the 18th and first part the 19th century was a sparsely populated, impoverished area. The Jewish communities were also poor and often asked for support from foreign communities. An example is the community in Hebron. The financial debts of the Jews in Hebron reached high levels and in 1811 they send Ysrael Halevi to ask for help from communities in the Diaspora (see link).

With the weakening global power of the Ottoman Empire Christians were allowed to rebuild churches and revive their communities. Religious motives were extremely evident for the Evangelical Templer movement. Fearing the Day of Judgement to be near they settled in Haifa, Jaffa and Jerusalem in hope of messianic salvation. (Although these Templers were citizens they were considered German enemies and were deported by the British in WWII see link).

In general the growth of Jewish and Christian communities continued until 1948 (and later) and can be clearly seen in the history of Churches and Synagogues that are still in use today. The church of Annunciation in the Old city of Jerusalem was build in 1848 by the Greek Catholic Patriarchate of Jerusalem. The separate existence of the Greek Catholic Church dates from 1724, when a split occurred in the ancient Greek Orthodox patriarchate of Antioch and a small group chose communion with Rome rather than Constantinople. Ever since this separate Byzantine or Melkite Church is tied to the Pope in Rome but follows the Byzantine rites and uses also Arab as languague. After the Greek Orthodox the Greek Catholics are the largest Christian Church in the Holy land with its largest community in the Galilee.

An interesting 19th century example of coexistence between different religions can be found in 1863 in Jaffa were Jane Walker–Arnott, the eldest daughter of a Glasgow University professor, founded the Tabeetha school. The school was aimed at improving the lives and independence of girls in a still oppressive society. The school admitted its first pupils, fourteen Christian, Jewish and Muslim girls on 16 March 1863 to a room In Jane Walker-Arnott’s house. The school expanded with help of Mr Thomas Cook, the renowned Travel Agent and purchased a plot outside the walls of the old city of Jaffa. This larger school is run by the Church of Scotland and was opened in November 1875. The school developed and until today it tries to serve boys and girls of all different faiths teaching both Hebrew and Arab languages, interfaith coexistence and they help children through intellectual learning, respecting and understanding of each other. (see link)

The Jewish Museum in London has a beautiful lithograph about Jewish women reading the scriptures in Jerusalem (1841) photo by wikimedia, David Wilkie.

%201845%20wikimedia.jpg)

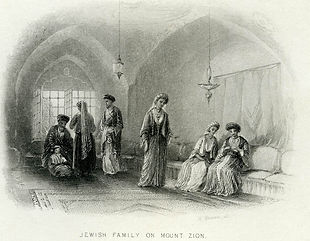

Jewish family, mount Zion Jerusalem, 1845. Wikimedia C.

JEWISH JERUSALEM

Jerusalem has always remained central to Judaism and the Jewish people because of its enduring importance and holiness. Rabbinic tradition has consistently affirmed Jerusalem’s eternal sanctity. For centuries, Jews around the world have turned toward the city in their daily prayers, expressing a constant spiritual connection. Throughout history, there has been a continuous Jewish presence in and around Jerusalem, with worship centered at the Western Wall and other sacred sites. Many of Judaism’s holy days commemorate events that took place in the city, reinforcing its role in Jewish memory and identity.

Since the 19th century Jerusalem became again the most important Jewish centre in Israel. According to Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, "In the second half of the nineteenth century and at the end of that century, Jews comprised the majority of the population of the Old City" (Jerusalem in the Nineteenth Century). Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1853 "assessed the Jewish population of Jerusalem in 1844 at 7,120, making them the biggest single religious group in Jerusalem and at the end of the 19th century (before the influence of the Zionist movement) Jews were more than half of the population of Jerusalem (absolute majority).

Wittenberg House in Jerusalem (photo Wikimedia C.)

This growth of Jewish influence in Jerusalem can still be seen Jewish religious buildings. The oldest synagogues in the old city of Jerusalem date back to the 8th-16th century but in the 19th century many new synagogues were established in Jerusalem. The beautiful Ohel Yitzhak, Menachem Zion, Tsemach Zedek and Tsuf Dvash synagogues are all more than 150 years old. Another fascinating building is the Beit Wittenberg (Wittenberg house). In 1867 the famous writer Mark Twain visited Jerusalem and he stayed in the Mediterranean Hotel that is closely located near Damascus Gate. He wrote at least one of the fifty letters that became the basis for his famous book "Innocents Abroad." In 1882 the property was bought and redeveloped into the Wittenberg House. The property of twenty apartments and a synagogue was developed by Moshe Wittenberg who arrived in 1881 from Belarus. Sadly the Jewish residents left the Wittenberg House in 1929 after Arab riots drove them away. In the 1980s however, former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon bought an apartment in this building and it houses now an educational centre.

Rishon Lezion Great Synagogue (1885 AD - photo Oren Valdman)

RELATIONS WITH THE ZIONIST MOVEMENT IN EUROPE

This website shows that modern Israel is build on foundations that go back far in time. This view opposes the opinion of Ahron Bregman who starts his well written book 'A history of Israel' with his conclusion 'that modern Israel started with the first Zionist congress'. Even in his book he writes that the first Aliyah happened before the first Zionist congress in Basel in 1902. Zionist ideas were much older as is described in previous chapters. In the 18th and 19th century important names that should be mentioned are Rabbi Judah Bibas (1789-1852), Rabbi Judah ben Solomon Hai Alkalai (1798–1878), Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kalischer (1795–1874), and philosopher Moses Hess (1812–1875). These people inspired the later Zionist movement just like the nationalist movements in all of Europe. Theodor Hertzl who successfully managed to popularise Zionism had experienced antisemitism in his life. He stated that the Dreyfus case turned him into a Zionist and that he was particularly affected by chants of "Death to the Jews!" from the crowds. Other scholars argued that the rise to power of the antisemitic demagogue Karl Lueger in Vienna in 1895 had a much larger effect in motivating Hertzl into pursuing a Jewish state. Herzl's Political Zionism was primarily the wish for a Jewish homeland to escape pogroms, antisemitism and prosecutions. Most refugees or migrants in the 19th century and first part of the 20th century to the Ottoman Empire were motivated by the prosecution and antisemitism. The genocidal pogroms of Eastern Europe and Russia, like for example the Kishinev Pogrom, made millions flee!

The millions of Jews that migrated had strong religious ties to Israel/Palestine. The Persian, Yemenite and other Middle East Jews who were deeply religious are important to remember. Their wish to return to Jerusalem was no 'Herzl invention' since religious Zionism is as old as the Torah. The religious motive to return to the promised holy land is part of Jewish religion ever since the Babylonian captivity. For some Jews, returning or even creating a state could help to pave the way for the return of the Messiah. However for most orthodox Jews creating 'a new state' was not an ultimate goal since that will only happen with the return of 'the Messiah'. But above all most immigrants were only trying to evade danger simply hoping for 'a future' instead of violence and they were certainly not all influenced by Hertzl's movement.

While Jewish immigration to the Vilayet of Syria and the Mutassarifate of Jerusalem was restricted Arab immigration was not restricted. This became important because when the economy was growing in the 19th and early 20th century more than 300.000 Arabs migrated to Ottoman Israel for mainly economic reasons (!) In contrast most Jews fleeing to Eretz Israel would from a 'modern human rights perspective' be seen as refugees fleeing prosecution. The refugees that arrived in Eretz Israel were sadly not met with 'Wir schaffen das' but rather with xenophobia, antisemitism and violent protests of the local (often Arab) population. The Arab attack on Petach Tikva in 1886 showed this clearly when a large group of Arabs attacked the residents of this new village (one person was killed and some others were wounded). But although violence and tensions were rising it is important to remember that most of the times the revolts and tragedies make the headlines while at the same time many people were living peacefully together in this fast growing country. There were hostilities between the Jews and Arabs, bt still not frequent.

Perhaps it is important to realise that Religious/Spiritual Zionism (return to sacred Mount Zion) is part of Judaism and to condemn this form of Zionism is equal to condemning 'pilgrimage' within Judaism, Christianity or Islam and so it is actually a form of antisemitism. Political Zionism could be criticised but actually one could argue that it is no longer relevant within modern day Israel. Perhaps Political Zionism ended with the creation of the state of Israel in 1948 and what remains is nationalism related to Israel and Religious Zionism related to Judaism.

SLAVERY IN OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Photo on Wikimedia commons: Shocking 'Painting (1872) of a rich Turkish man examines a naked boy, before buying him."

Just like in the Roman Empire and many other empires in history cruel and inhumane slavery existed as an accepted fact and part of economic life. Also slavery in the Ottoman Empire, until the beginning of the 20th century, was both legal and of great importance for the Ottoman Empire's economy and traditional society. Often slaves were obtained through wars and special expeditions in South and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. Between the 15th and end of the 19th century approximately 2,5 million slaves were taken from nearby countries! Slavery existed in different forms and many slaves became high officials and could regain their freedom in the Ottoman Empire. On the other hand most slaves were not as fortunate and romanticising successful stories of slaves neglects the incredible pain and suffering of the mostly poor and abused slaves!! In the first half of the 19th century the demand for slaves in the Ottoman Empire even increased. Not only slaves from the Caucasus and central Asia were taken into captivity but also African slaves, from the Sudan, Senegal, Ethiopia and other countries in Africa. The were also sold in Markets for work in urban domestics, municipal services, in industry, and in other dangerous and disdained occupations. Women often were kept and abused in harems as slave-girls or concubines.

Up until 1908 female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire and sexual slavery was always a central part of the Ottoman slave system. Until the late 19th century also within certain elite Jewish families slavery existed. A detailed account of Sarah La Preta, a female slave of Ethiopian origin that worked in the household of a elite Jewish family in Jerusalem sheds a light on the way the shocking practice of slavery still existed in different ethnic groups during the Ottoman Occupation.

WORLD WAR I & END OF OTTOMAN OCCUPATION

World War I profoundly reshaped Ottoman Syria and Palestine, leaving both immediate humanitarian consequences and long-term geopolitical transformations. During the First World War the region was a major front in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, part of the broader Middle Eastern theatre of the war.

Hostilities began in 1915 with an unsuccessful Ottoman raid on the Suez Canal, prompting the British to form the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). By 1916, British forces had regained the Sinai Peninsula, and in January 1917, they completed this effort at the Battle of Rafa. Despite initial setbacks in Gaza, the British—supported by the Arab Revolt—eventually pushed the Ottomans out of Palestine. The campaign concluded with the Armistice of Mudros in 1918, marking the collapse of Ottoman control in the region.

Australian, English, New Zealand & Indian

cameliers in Palestine.

.jpg)

Gaza in ruins, 1918

Graves from unknown victims of the Jaffa and Tel Aviv deportations. photo Yanay, wikimedia C

Scots Memorial Church, Jerusalem honouring the fallen Scottish soldiers during WWI. (photo Shaula Haitner)

One of the most severe wartime episodes in the region was the expulsion of Jewish communities by the Ottoman authorities. In 1914, approximately 6,000 Russian Jews were deported from Jaffa, labeled as enemy nationals following the Ottoman Empire’s entry into the war alongside the Central Powers. The situation worsened in April 1917, when 10,000 Jews were forcibly expelled from Jaffa and Tel Aviv under orders from Djemal Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Greater Syria (see link). This was motivated by growing Ottoman suspicions of Jewish sympathies and alleged collaboration with the British and the Ottomans harsch reaction to all Seperatist movements (Arabs and Jews). Should the Turks be driven from Palestine, threatened Djemal Pasha, "no Jews would live to welcome the British forces". (see link). The expulsion resulted in widespread suffering, including violence, starvation, exposure, and an estimated 1,500 deaths. While Muslim deportees were later allowed to return, Jews were barred from returning until the British advance in 1918.

Although these deadly expulsions were often seen as a harshly disproportionate response rooted in Djemal Pasha’s anti-Zionist stance it is important to notice that Djemal Pasha in 1918 supported a Jewish Homeland in Palestine. In a meeting in Istanbul on August 12, 1918, Grand Vizier Talaat Pasha gave Leopold Perlmutter, a German Jewish businessman and a personal acquaintance, an official statement on behalf of the Ottoman government: "I declare once again, as I already did to the Jewish delegation, my sympathies for the establishment of a religious and national Jewish center in Palestine by well-organized immigration and settlement, for I am convinced of the importance and benefits of the settlement of Jews in Palestine for the Ottoman Empire. I am willing to put this work under the high protection of the Ottoman Empire, and to promote it by all means that are compatible with the sovereign rights of the Ottoman Empire and do not affect the rights of the non-Jewish population." This was later named the Turkisch Balfour declaration.

The war’s end ushered in a radical redrawing of the political map through the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The League of Nations mandates granted France control over Syria and Lebanon, while Britain took Palestine and Mesopotamia (Iraq). The Republic of Turkey emerged in 1923 following the Turkish War of Independence, while other modern states—including Iraq (1932), Lebanon (1943), Transjordan and Syria (1946), and Israel (1948)—gradually came into existence as the mandates ended. Thus, World War I not only inflicted grave humanitarian consequences, particularly on the Jewish communities of Palestine, but also laid the foundation for the modern Middle Eastern state system, the consequences of which continue to shape regional politics to this day.

ARAB REVOLT & MAC MAHON CORRESPONDENCE

In these years the Arab Revolt in the Ottoman empire began in 1916 with British support and this Arab uprising against the Ottoman Occupation helped to turn the tide of the war in the Middle East. On the basis of the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence, an agreement between the British government and Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca, the revolt was officially initiated at Mecca on 10 June 1916. The Arab nationalist goal was to create a single unified and independent Arab state stretching from Aleppo in Syria to Aden in Yemen, which the British had promised to recognise. MacMahon explained that Palestine was not included in this Arab state. See picture of part of the letter. Following the Sykes-Picot Agreement, the Middle East was later partitioned by the British and French into mandate territories. There was no unified Arab state, much to the anger of Arab nationalists.

(Armenian refugees in Jerusalem 1918)

ARMENIAN GENOCIDE REFUGEES OF JERUSALEM

A point of notice is also the migration to Israel because of some Armenian refugees fleeing because of the Armenian Genocide in 1917. In 1915 the Ottoman government and Kurdish tribes in region started the extermination of its ethnic Armenian population, resulting in the death of up to 1.5 million Armenians in the Armenian genocide! The genocide was carried out during and after World War I. It led to the mass-killing of the able-bodied male population through massacre and subjection of army conscripts to forced labour. It was followed by the deportation of women, children, the elderly and infirm on death marches leading to the Syrian desert. The women and children were deprived of food and water and subjected to periodic robbery, rape, and systematic massacre. Large-scale massacres were also committed against the Empire's Greek and Assyrian minorities as part of the same campaign of religious & ethnic cleansing. But also Jews were persecuted by the Ottoman empire in these terrible years of human history (see also: article Armenian Refugees). If one looks at all the mass killings and prosecution in the Ottoman empire in these years the conclusion seems to be that the Armenian genocide was a Christian (see article) or religious genocide! This genocide had already been started in 1894 when the Hamidian massacre started. This genocide according to historians was the deliberate and brutal killing of between 80,000 to 300,000 innocent people. The Hamidian massacres was the main reason for migration of Jews from Anatolia and these 'Urfa Jews' settled for example in the Nahlaot neighbourhood of Jerusalem (See Urfalim Synagogue).

Many countries including Israel (see article) acknowledge the mass killings. They still neglect that all these killings were premeditated and planned on a large scale making it truly genocidal and an unimaginable horrific period for all victims and survivors. Hopefully this will change very soon by looking at facts stored in the Armenian Genocide Archives of Jerusalem!

GROWING ROLE OF WOMEN

19th & early 20th century

WOMEN IN THE 19TH CENTURY CATHOLIC CHURCH

At the end of the 19th century the acceptance of women was growing in society although true equality only came in the second half of the 20th century. This could also be seen in the Catholic church. In 1888 Pope Leo XIII authorised the entrance of women in the order of the Holy Sepulchre who contributed to the Christian communities in the holy land. And recently Pope Pope Francis canonised two 19th-century nuns of the former Ottoman Sanjak of Jerusalem;

-

Marie Alphonsine Ghattas - who was born to a Palestinian family in Jerusalem - co-founded the Congregation of the Rosary Sisters, which today runs many kindergartens and schools. See also Sisters of the Rosary convent)

-

Sister Mariam Baouardy, who founded a Carmelite convent in Bethlehem

Picture of Marie Alphonsine Ghattas - photo Tamar Hayardeni

'WONDERWOMAN' OF WORLD WAR I

During World War I, Sarah Aaronsohn a spy fought to free Eretz Israel/Palestine from Ottoman Occupation. She withstood torture for her ideals but she committed suicide after arrest by Turkish authorities and was later described as a Jewish 'Joan of Arc'. The semi-military role Sarah carved for herself, her contribution and her sacrificial death made her an icon and a model of a new “Hebrew” femininity. To learn her story it is recommended to read 'A Tale of Love and Destiny' by Barry Shaw (2022).

picture Sarah Aaronsohn, the Jewish 'Joan of Arc'

.jpeg)

%20Godot13.jpg)

_heic.png)

_with_a_depiction_of_Jerusalem_-_Google_Art_Project%20(1).jpg)